Words have meaning. They symbolize ideas, complex concepts. Otherwise, they are merely collections of accumulated letters. Language, or lack thereof, informs the ways in which we navigate life, respond to stimuli, and interact with each other.

WORD PLAY: Language As Medium, is a tightly curated exhibition on view at The Bonnier Gallery in Miami, Florida through July 20, 2019. It features works by artists Fiona Banner, Benjamin Bellas, Mel Bochner, David Moreno, Kay Rosen, and Damon Zucconi, and slyly explores the philosophical underpinnings of language. The exhibition's catalogue essay provides the viewer with an overview of the role of language as conceptual art within the context of Postwar Art.

On June 3rd, 1967, Virginia Dwan initiated the first in a series of four exhibitions between 1967 and 1971 in her New York City space that explored the role of words and language within visual culture. It marked the Dwan Gallery's departure from exhibiting Postwar artists, like Yves Klein, Ad Reinhardt, and Robert Rauschenberg, in her Los Angeles gallery to actively championing the New York avant-garde associated with the burgeoning Minimalist and Conceptualist movements. Dwan was at the forefront. The first of these shows titled, "Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Read," was primarily sculptural, and featured works by Carl Andre, Arakawa, Walter De Maria, Dan Flavin, On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, and Robert Smithson, among others. Smithson's press release for the show, written as Eton Corrasable, a nom de plume derived from Eaton's Corrasable Bond erasable typewriter paper, declares:

"Language operates between literal and metaphorical signification. The power of a word lies in the very inadequacy of the context it is placed, in the unresolved or partially resolved tension of disparates. A word fixed or a statement isolated without any decorative or 'cubist' visual format, becomes a perception of similarity in dissimilars ˗ in short a paradox."

In essence, words function as indicators of the limits of language in constructing knowledge, and similarly, Smithson asserts that language is "built, not written." The medium is not always the message, as philosopher and post-modern media theorist Marshall McLuhan would lead us to believe. Or, as artist Mel Bochner exhibited in Dwan's "Language IV" show, "Language is not transparent."

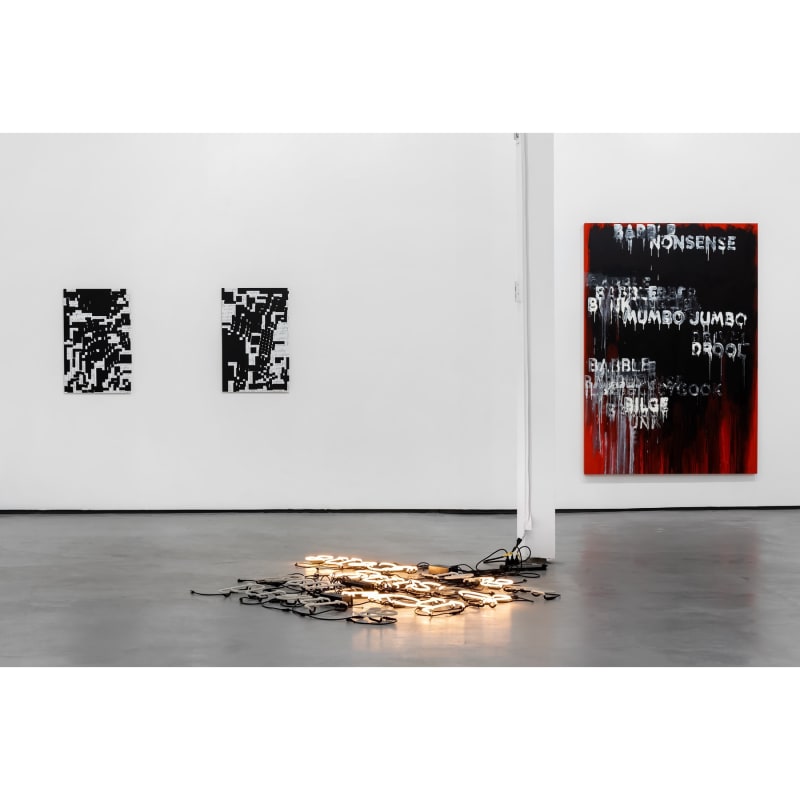

It is apt that the exhibition's organizers selected Damon Zucconi's work, Corrasable, for inclusion. Immediate references to Smithson aside, it recalls Robert Rauschenberg's creation of Erased De Kooning. The younger generation, in this case Zucconi, deftly engages with art historic precedent while making his own mark on erasable typewriter paper, a quasi-palimpsest. Zucconi's other pieces recall early computer codes superimposed over handwriting in crossword puzzle-like patterns.

Benjamin Bellas' aptly titled, Seletti's Neon Art Lights Rearranged To Display, One Line At A Time, David Shulman's Poem Washington Crossing the Delaware Over the Course of An Exhibition, is perhaps, one of the most referential works on display. At first glance, the illuminated and unlit neon letters arrayed on the gallery floor hearken the commercial cacophony of lights in New York's Times Square and Dan Flavin's sculptural fluorescent bulbs. Bellas' use of pre-fabricated signage alludes to puckish Duchampian Dada ready-mades, though his application of materials reads less whimsical and more direct. Upon closer inspection, this colorful alphabet soup concocts an anagram, similar to David Shulman's sonnet, which serves as Bellas' source. Shulman's poetry, and in turn Bellas' installation, illustrates the poet's experience viewing German-American artist, Emanuel Leutze's, epic 1851 oil on canvas housed for more than a century at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Suddenly, these simple neons transform and illuminate McLuhan's critical theory that "the medium is the message," as "a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence." However, as Smithson posits, Bellas' work extends beyond its physical environment and launches the viewer into metaphorical space, grey matter, as it were.

Like Bellas, Kay Rosen's work confronts the viewer with another literary reference, this time both typographic and Shakespearean. Star Crossed serves as visual representation of the prologue in Romeo and Juliet. In the play, the verse is narrated by a chorus, the language replete with paradox. Likewise, Star Crossed depicts a critical tension between the houses of Montague and Capulet, the "star crossed" lovers, and their tragic fate. The impermanence of the installation echoes the ephemerality of life, juxtaposed against the clear iconography of the asterisk and "X." While Star Crossed references literature, Rosen's Rear Area and Sombra Sobre El Hombre (Shadow Over the Man) visually recall the typography of On Kawara's Today series. The critical difference: Rosen's facility with formal linguistics lends her work a subtlety and wit as words and meaning morph, revealing the unexpected, while Kawara's Date paintings document the language and syntactical conventions of the place in which the piece was created, denoting a distinct moment in time.

While the afore-mentioned artists engage with literature and written symbols and words, Fiona Banner and David Moreno actively explore the structural nature of language and punctuation. In his works, Moreno physically deconstructs books (Emptyful) representing words using parentheses, periods, and spaces to denote individual words within the lexical formats inherent in written speech. In Words Give Birth to Themselves, he provides graphic illustration of etymology. Banner's Versus Versus (Invisibles) also addresses the structural constructs of the written word via redaction of entire paragraphs indicated by the ¶ mark. In this way, she directs how the viewer parses a text. In Vs., Banner, explores homonyms and the juxtaposition of spoken and written language and meaning.

The Bonnier Gallery is a new presence in the growing Miami art milieu. Grant and Christina Bonnier aim to bring a different sensibility to South Florida, leveraging their experience with the masters of Minimalism and Conceptualism. Grant, son of Peder Bonnier, a former gallerist and a near-legendary private dealer, sees an opportunity to amplify increasing intellectual quality of exhibitions at the ICA and Bass Museum. Also, Grant and Christina's initiative complements that of Inigo Philbrick, the London dealer who recently opened a new, satellite exhibition space in Miami's Design District. The Bonnier Gallery's summer programming will be organized by guest curators. This year, the gallery retained LinnPress, specialists in contemporary art, to organize an exhibition that would bring life to Conceptualism, span multiple generations and, most significantly, offer respected, collectible art at a range of prices ˗ from $8 to $225,000 ˗ helping to stimulate and build the collector base.

To reference the semantics of Mel Bochner's painting, Blah, Blah, Blah, this exhibition is anything but.